AC Hotel Set to Impact Spartanburg’s Cultural Landscape through Art, European Influence

March 3, 2016 | Development

OTO Development announces the creative direction of their AC Hotel Spartanburg, SC (slated to open 2017). The forthcoming hotel will take a unique approach to AC by Marriott’s design-driven brand by featuring a carefully curated collection of modern art. On extended loan from the Johnson Collection, paintings and sculpture created by faculty members and students at the experimental arts enclave of Black Mountain College will be highlighted throughout the property, underscoring the hotel’s sophisticated aesthetic, European influence, and Southern connection.

Sequestered in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, Black Mountain College was a living laboratory for creative experimentation and interdisciplinary collaboration, attracting artists, musicians, dancers, poets, and thinkers from around the world. Operating between the years 1933 and 1957, the school’s roster included luminaries of the burgeoning modern art scene—groundbreaking artists who would play vital roles in shaping twentieth century aesthetics. Many of the school’s leaders—including the school’s longtime director and Bauhaus master Josef Albers—were intellectual refugees who had fled Nazi oppression. Robert Rauschenberg, Kenneth Noland, Robert Motherwell, Elaine de Kooning, Buckminster Fuller, Ilya Bolotwsky, Ruth Asawa, and Esteban Vicente are among the artists whose work will be featured at the downtown hotel.

Black Mountain College represented a wholly unique and pivotal moment in American art history. Erin Corrales-Diaz, Curator of the Johnson Collection, notes that the school’s progressive spirit and international perspective inspired “artistic philosophers and practitioners to freely push artistic boundaries. The college’s emphasis on imagination and independence unleashed a tide of creative innovation that continues to influence contemporary art. That this current of avant-garde experimentation was happening in the mid-twentieth century South—and only an hour’s drive from Spartanburg—is a revelation to most audiences.”

Known in hospitality as a sleek, design-driven brand, AC Hotels are intended to be a lifestyle experience. Founded in Spain, AC was acquired by Marriott in 2011, and was imported into US markets in 2014. “Blending Black Mountain College’s bold aesthetic with AC Hotels’ timeless modernity is a perfect match,” comments David Henderson, Director of the Johnson Collection. Pieces created by iconic modern artists will be placed throughout the hotel. “To showcase works of museum caliber is atypical in hospitality and we are thrilled to make them available to our community and guests,” OTO’s CEO, Corry Oakes, said. “We’re enhancing the guest experience in a unique way, and bringing light to an important time in art history.”

A recent resurgence of interest in Black Mountain College’s import is underscored by a major exhibition presently touring prestigious museums across the United States; a companion catalogue of the same title, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College, 1933-1957, was published by Yale University Press. Both projects include paintings from the Johnson Collection, a private collection dedicated to fine art of the American South. Currently, many of the collections Black Mountain objects are on display at TJC Gallery in Spartanburg, SC until May 27. For a list of gallery times and more information on the collection, please visit www.thejohnsoncollection.org.

ABOUT THE ARTWORK:

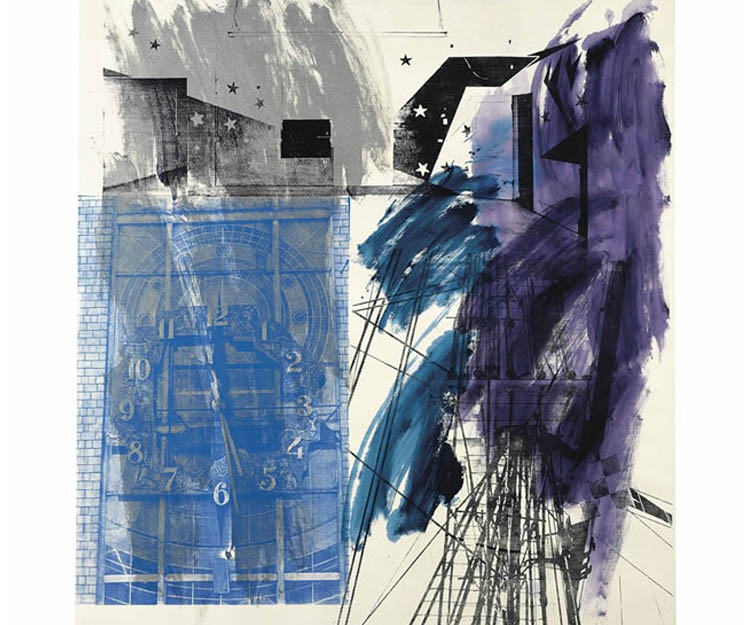

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG (1925–2008)

Time + Ties, 1990

Robert Rauschenberg was a remarkably versatile talent and innovative technician who embraced abstraction, photography, borrowed sources, and tangible objects to create a repertoire of imagery uniquely his own—most notably, his signature two and three-dimensional “combines.” He was based in the SoHo district of New York in the early 1950s when Abstract Expressionism raged, but pivotal to his evolution as an artist was the time he spent at Black Mountain College, as both student and artist-in-residence.

Robert Rauschenberg was a remarkably versatile talent and innovative technician who embraced abstraction, photography, borrowed sources, and tangible objects to create a repertoire of imagery uniquely his own—most notably, his signature two and three-dimensional “combines.” He was based in the SoHo district of New York in the early 1950s when Abstract Expressionism raged, but pivotal to his evolution as an artist was the time he spent at Black Mountain College, as both student and artist-in-residence.

Born in Port Arthur, Texas, Rauschenberg joined the Navy in 1944 and afterward studied on the GI Bill at the Kansas City Art Institute and in Paris. He first went to the experimental enclave at Black Mountain in the fall of 1948, staying through the next summer. His encounters with Josef Albers, the domineering head of the art curriculum, were fraught with tension. Albers heartily disapproved of the freewheeling young artist; nevertheless, Rauschenberg learned much from the German master, especially in regard to color theory and combining different materials and textures, the focus of a course called “Surfaces.”

Rauschenberg maintained important liaisons with many creative individuals: the musician John Cage and the dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, whom he met at Black Mountain; and the artists Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns. The interaction with Johns was particularly dynamic; they worked together as window designers for Tiffany’s and Bonwit Teller’s, disdained Abstract Expressionism, and encouraged one another to pursue their individual artistic visions.

Much of Rauschenberg’s oeuvre is autobiographical. The most classic example is Bed, the 1955 combine in which he used his own bed—complete with sheets, quilt, and pillow—as the canvas for a painting. Soon after, in 1963, the Jewish Museum in New York gave Rauschenberg his first career retrospective, which helped to launch him on the international stage the next year at the Venice Biennale. The ensuing years saw many exhibitions at such prestigious museums as the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Centre Pompidou in Paris. In addition to his achievements as a visual and performance artist, Rauschenberg was also a political activist opposed to the war in Vietnam. In 1984, he established the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI), a philanthropic initiative aimed to promote understanding through artistic dialogue.

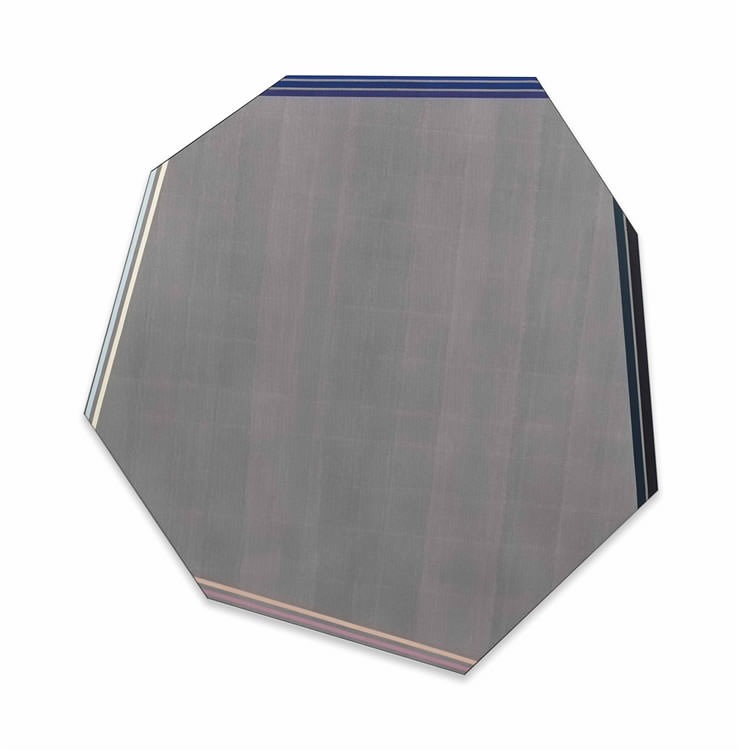

KENNETH NOLAND (1924-2010)

Avanti Adios, 1978

Kenneth Noland, a native of Asheville, North Carolina, was one of the few “local boys” to study at the progressive Black Mountain College, attending from 1946 to 1948, and again in 1950. Thoroughly steeped in the abstract idiom, Noland emerged as an articulate Color Field painter who relied on a geometric foundation. Through his teachers Ilya Bolotowsky and Josef Albers, he learned the importance of geometrical relationships and color theory. Under Bolotowsky, with whom he had a great personal affinity, he was forced to reckon with Neoplasticism and the heritage of Piet Mondrian; from Albers, Noland acquired problem-solving skills and a talent for working in series.

Kenneth Noland, a native of Asheville, North Carolina, was one of the few “local boys” to study at the progressive Black Mountain College, attending from 1946 to 1948, and again in 1950. Thoroughly steeped in the abstract idiom, Noland emerged as an articulate Color Field painter who relied on a geometric foundation. Through his teachers Ilya Bolotowsky and Josef Albers, he learned the importance of geometrical relationships and color theory. Under Bolotowsky, with whom he had a great personal affinity, he was forced to reckon with Neoplasticism and the heritage of Piet Mondrian; from Albers, Noland acquired problem-solving skills and a talent for working in series.

Noland had served in the United States Air Force during World War II and used the GI Bill to underwrite a sojourn in Paris where he studied with Ossip Zadkine, a Russian-born artist best known for his cubistic sculptures. Upon his return, Noland settled in Washington, D.C., and became good friends with Morris Louis, whose technical facility with acrylic paint influenced him. Of the two, Noland was the more gregarious, enjoying annual visits to New York and regular contact with the mainstream. After a pivotal visit to Helen Frankenthaler’s studio in 1953, Noland and Louis had an intense period of collaboration, one that has been equated to a jam session of jazz musicians. Together they experimented with the new acrylic paints, particularly in regard to staining. Whereas Louis consistently retained the spontaneity of Abstract Expressionism in his staining and soaking of raw canvas, Noland focused upon flat geometric shapes and pure colors—choices reflective of his lessons at Black Mountain.

Noland's approach is wholly formalist, and he began to work on a large scale in the early 1960s, experimenting with various formats, including diamonds, tondos, lozenges, and chevrons. His interest in unorthodox shapes may have derived from his teacher Bolotowsky. Typically, Noland painted with his canvas on the floor; during the creative process, he would climb a ladder, gaining an aerial view that mirrors his experience as an Air Force pilot.

North Carolina recognized its native son on a number of occasions; in 1995 he was given the North Carolina Award in Fine Arts, and two years later Davidson College awarded him an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts. More recently, in 2004, the Museum of Fine Art in Houston, Texas, organized a major exhibition of his work, followed by an installation of his striped paintings at the Tate Museum in London. Noland’s work is represented in the collections of prestigious international and national museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. He died of kidney cancer at his home in Port Clyde, Maine, in early 2010.

RUTH ASAWA (1926–2013)

Untitled

Born in California to Japanese immigrants, Ruth Asawa battled entrenched discrimination throughout her life to become this country’s first Asian American woman sculptor of note and a force for arts education. She invented ingenious wire pieces and created so many outdoor works in San Francisco that she became known as the “fountain lady.” Today, her work—praised for its “gossamer lightness “—is represented in prestigious national museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Guggenheim Museum among others.

Born in California to Japanese immigrants, Ruth Asawa battled entrenched discrimination throughout her life to become this country’s first Asian American woman sculptor of note and a force for arts education. She invented ingenious wire pieces and created so many outdoor works in San Francisco that she became known as the “fountain lady.” Today, her work—praised for its “gossamer lightness “—is represented in prestigious national museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Guggenheim Museum among others.

While her parents labored as truck farmers in Norwalk, California, young Ruth attended local schools and drew from an early age; she also went weekly to a Japanese cultural school where she studied language and calligraphy. In 1942, her family was among the 120,000 Japanese-Americans interred along the Pacific coast. They were initially incarcerated at the Santa Anita racetrack stables—where artists from Walt Disney led classes in drawing—before being relocated to a camp in Rohwer, Arkansas.

Underwritten by a scholarship from the Quakers, Asawa studied art at Milwaukee State Teachers College. Professional certification required that she perform student teaching, but Asawa was denied the necessary placements based on her Japanese heritage. Instead, she enrolled at Black Mountain College, studying there from 1946 to 1949. She became a devoted student of Josef Albers, who stressed the importance of materials, and benefited from the inventive structural methods of architect Buckminster Fuller and the improvisational approach of dancer Merce Cunningham.

In 1945 and again in 1947, Asawa traveled to Mexico where she learned how to crochet baskets, a technique she later applied to her wire sculptures, which often hang from the ceiling. Living in San Francisco with her husband and six children, Asawa struggled to make ends meet. Working on her woven and tied wire pieces at night, she gradually attained some recognition in solo and group exhibitions. Despite some early successes, her work was frequently labeled “woman’s work” or “craft” because it resembled basket weaving.

When she realized how little art was being taught in local schools, Asawa helped to establish the Alvarado Arts Workshop, an organization that eventually arranged for professional artists to instruct students in fifty area schools. In 1982, she devised the School of the Arts high school near the city’s cultural center. The school was renamed Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts in 2010. That same year, Asawa was given a Bachelor of Fine Arts by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, more than fifty years after being denied her teaching certificate. In reflecting on the injustices that marked her journey, Asawa revealed no bitterness: "I hold no hostilities for what happened; I blame no one. Sometimes good comes through adversity. I would not be who I am today had it not been for the Internment, and I like who I am."